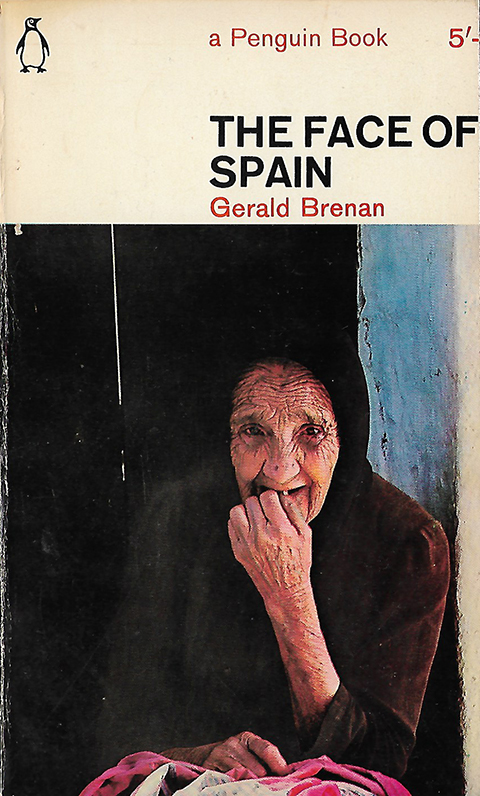

Een tekst van Gerald Brenan. Onderstaand stuk speelt in Madrid.

Zie een andere tekst van Brenan onder Verhalen » South from Granada.

The hotel where we are staying is in the Gran Via, that vulgar and blatant street of dwarfed skyscrapers that cuts through an old quarter. It is new and run on modern lines. We have a bedroom and private bathroom with excellent and lavish food for 15s. a day each and a view from the window of the distant mountains.

The number of waiters in this hotel astonishes me. In the dining-room there are fourteen, dressed in white jackets at lunch and in evening dress at dinner, but with various additions of insignia to show their waiterly rank. Upstairs there are not only the valets de chambre who bring breakfast, but the camareros de piso who carry other meals to one's room if they are required. In addition to these there are also of course the various chambermaids, each with their different hours and functions, the washerwomen who occupy the roof, and the lift boys who are learning English. Every time we go up or down we give them a lesson. Really this relatively modest hotel - there are a dozen larger and more expensive in Madrid - is organized with the same lavishness of personnel and attention to hierarchy as the old houses of the nobility.

The Spanish waiters make up one of the most striking and representative types in the country. With their thick eyebrows and erect, stylized pasture they have the air of bullfighters manqués, of toreros who wisely prefer the white napkin to the red cloth and the pacific diner to the charging bull. They move with the same litheness and ballet dancer's precision and put a certain solemn operatic air into every gesture. How refreshing to see people doing the supposedly humdrum and mechanica! things with artistic relish and gusto! It is something that the Englishman, accustomed to the utilitarian outlook of his countrymen, to their mixture of sloppiness and Puritan philistinism, can hardly understand. It makes one realize the price we have had to pay for Locke's and John Stuart Mill's philosophy. We can hardly conceive of our dinner as a waiter's ballet - quick, yet with the gravity and seriousness generally to be expected of Spanish things. Yet that is what in this country it may easily be.

But what about the food? Spanish cooking, it must be admitted, has no claims to compete with French. It consists of little more than a selection of the peasant dishes of the various provinces, with a few supplements from other countries. But the materials are good and trouble is taken in their preparation. The only defect I find is that of monotony. Spaniards think of a mea! as of a religious service. Just as the introit leads up to the gradual, so the soup introduces the omelette, the omelette paves the way for the fish - in which there is about as much variety as there is between one collect and another - and the fish ushers in the clinching part of the meal, the veal cutlet or beef steak. But an Englishman will find absolutely no cause for grumbling till he has been living in a Spanish hotel for at least a month. And in the excellent but expensive restaurants of Madrid he will get all the variety that he needs.